Debt, Delinquency and Racial Disparities in Massachusetts

By Alyssa Haywoode and Peter Ciurczak

Debt has several faces. Borrowing money for long-term investments can be beneficial because it allows individuals or businesses to leverage capital they don’t currently have to invest in opportunities that can yield strong returns over time. Taking out a student loan, for example, can help someone build human capital that increases long-term earning potential. Counterintuitively, more debt can be a benefit if borrowers are able to make regular payments and if the investment yields returns that exceed the cost of borrowing.

But often debt becomes an onerous burden, from high-interest credit cards that lock households into unaffordable payments to medical debt that seems too large to tackle. This debt makes it difficult to accrue wealth, drains disposable income, and threatens to become delinquent debt that can ruin borrowers’ credit scores.

Even within debt types, debt can be a double-edged sword. Taking out a mortgage, for example, helps some borrowers buy homes that will appreciate over time, helping to generate wealth. But not all mortgages are the same. One cause of the Great Recession, for instance, was the proliferation of predatory home loans with confusing terms, like interest rates that increased over time. This left many borrowers vulnerable to foreclosures and substantial loss of wealth. Similarly, student loans help many borrowers move into successful careers as nurses, teachers, and engineers. But borrowers who attend some for-profit schools can end up with high monthly loan repayments not worth the degree they may or may not have received.

What makes the dual nature of debt even more complex are the underlying patterns of racial disparities. This is an issue we explored in Debt: Exploring Wealth Beyond Assets, a virtual event on May 9, 2024, in the Racial Wealth Equity Research and Conversation Series, featuring research from the Aspen Institute’s report Disparities in Debt: Why Debt is a Driver in the Racial Wealth Gap. In this research brief, we highlight some key findings from Aspen’s work and pair it with some additional analysis of our own.

Racial Wealth Equity Research and Conversation Series – Debt: Exploring Wealth Beyond Assets from The Boston Foundation on Vimeo.

The Aspen Institute’s report concludes that, “Compared to white people, the debt held by people of color is: 1) more likely to be harmful; 2) more likely to involve the court system; and 3) more likely to have spillover non-financial consequences.” These are useful points to keep in mind as we explore debt through the remainder of this piece.

Debts by Group

Debt loads vary by racial group. Nationally, Asian families hold the most debt, around $240,000 at the median, meaning that 50 percent of households hold more than that amount of debt, and 50 percent hold less. White families have $94,000 in debt at the median. And Black and Latino families have half that amount, around $45,000 and $40,000, respectively. This is somewhat counterintuitive in that the highest wealth racial groups (Asian and White) have the highest levels of debt, but ultimately this speaks to the fact that debt can serve to support wealth creation and the fact that those with greater wealth can also afford to borrow more.

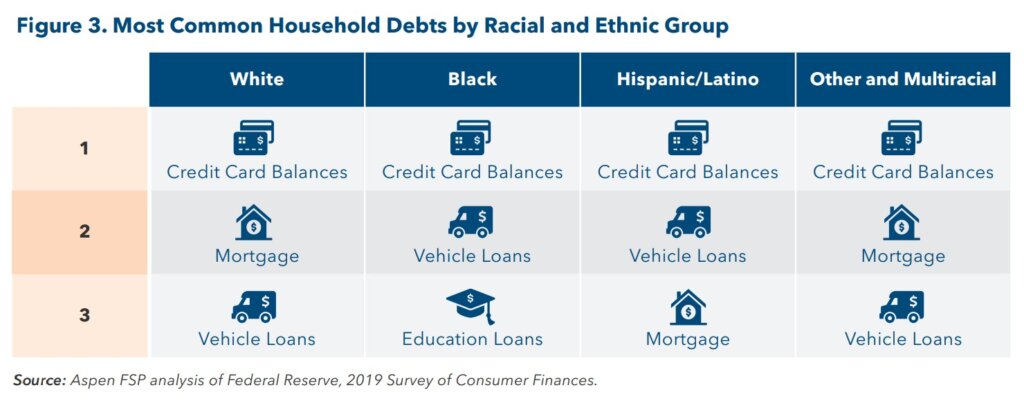

The most common type of debt for all groups is credit card debt, but it diverges from there. After credit card debt, White (and Other and Multiracial) households are more likely to have mortgage debt—that presumably allows these groups to build wealth. Notably, mortgages do not make the top three debt types for Black households, the only group for which this is the case. Instead, vehicle and education loans round out this group. And even if education loans aren’t put toward for-profit colleges (as mentioned earlier), the debt load from a four-year degree may still be difficult for some to overcome. Indeed, Black student loan borrowers are “especially likely” to have student loan debts that leave them with a negative net worth.

While Asian and White families tend to hold more debt, some of this may be due to limited access to debt for Black and Latino families. White households, for example, tend to have easier access to debt to launch businesses. As we found in our 2021 report, for instance, The Color of the Capital Gap, Increasing Capital Access for Entrepreneurs of Color in Massachusetts, Black business owners often can’t access business loans at all. The report notes that 38 percent of Black-owned firms received none of the financing they sought, compared to only 20 percent of White-owned firms. And while only 31 percent of Black-owned firms received 100 percent of the financing they sought, 49 percent of White-owned firms did.

Debt Delinquency by Group

One way to home in on where debt becomes a problem is to look at delinquencies. With the recent exception of medical debt, delinquency can lower credit scores, limit the ability to accrue wealth, and expose borrowers to collections and court actions. While there aren’t good measures of delinquencies at the individual or household level, the Urban Institute analyzed delinquencies at the ZIP Code level through Debt in America: An Interactive Map. This allowed them to differentiate between ZIP Codes with predominantly White populations and ZIP Codes predominantly comprising people of color. Nationally, 26 percent of Americans carry delinquent debt, including 22 percent of people in predominantly White ZIP Codes and 35 percent in ZIP Codes of color, according to the Urban Institute (national and Massachusetts figures excerpted below).

In Massachusetts, the overall level of delinquency is lower but racial disparities are slightly worse: 17 percent of Massachusetts residents carry delinquent debt, including 14 percent for predominantly White ZIP Codes and 31 percent for predominantly ZIP Codes of color.

The Urban Institute analysis also allows us to break out delinquencies by four categories of debt, as shown in the interactive graph below. And there’s some good news here: other than for credit cards, delinquencies are meaningfully lower in Massachusetts than nationwide. Further, the largest difference is with medical debt. Just four percent of Massachusetts residents are behind on these payments, as compared to 13 percent of Americans. This is likely a result of Massachusetts having among the strongest health-care systems in the country, with a robust subsidized health-care system for lower-income residents.

Delinquency shares are closer for other types of debt, though student loan defaults are worth highlighting. Massachusetts residents are more likely to have higher shares of student loan defaults than any other type of delinquency, perhaps due to the state’s large college-educated population. This share is still lower than national figures, however.

When broken out by race, ZIP Codes of color in Massachusetts tend to have more than double the share of delinquent debt than in predominantly White ZIP Codes, except for medical debt. Nevertheless, ZIP Codes of color in Massachusetts still have lower delinquency rates than similar communities across the United States.

Debt Can Help, Debt Can Harm

Paradoxically even when debt is used in positive ways to build wealth—through home purchases or by financing a college education—these appropriate uses can increase racial wealth gaps. Families with more wealth to begin with can afford to borrow more and are often able to take on loans with more favorable terms. These investments often yield greater returns, widening gaps over time.

It will take careful consideration to balance the advantages and disadvantages of “good” and “bad” debt. And to address racial debt disparities, it’s essential to create debt products that have fair terms and conditions that protect borrowers from falling into debt traps that they can’t escape. Eventually, debt should become a useful tool for all borrowers, regardless of race.